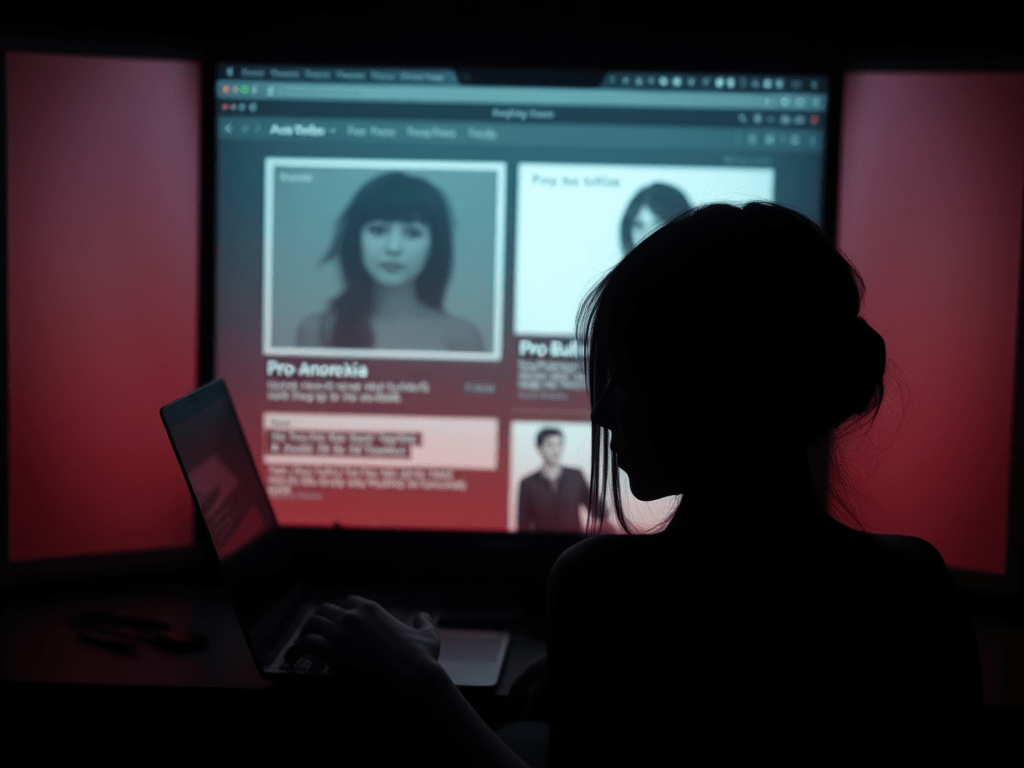

The first time I saw the terms “Ana” and “Mia” was on a forum called MyProAna. I was sixteen, already six months into restricting behaviors that had begun as a “healthy lifestyle change” and morphed into something more sinister. Ana and Mia—cutesy nicknames for anorexia and bulimia—were personified as demanding friends, sometimes cruel taskmasters, occasionally comforting companions. The site was filled with “inspiration” photos, restrictive diet plans, and competition threads where users compared weights, calories, and behaviors.

What began as curiosity quickly became obsession. Within weeks, I was deeply embedded in online communities that normalized and even glorified disordered eating. These spaces claimed to offer “support,” but the support wasn’t for recovery—it was for becoming more efficient at self-destruction.

Eight years and five treatment attempts later, I understand how these communities nearly cost me my life while paradoxically offering a twisted sense of belonging I couldn’t find elsewhere. This is my story of descending into eating disorder communities, the physical and psychological damage that followed, and the complicated path toward actual recovery.

MyProAna and the Online Subculture of Eating Disorders

The pro-anorexia (“pro-ana”) and pro-bulimia (“pro-mia”) online subculture exists in surprisingly plain sight. Despite periodic platform crackdowns, sites like MyProAna continue operating with thinly-veiled disclaimers about “not promoting eating disorders” while their content does exactly that.

What I found most seductive about these communities wasn’t just the weight loss tips or the validation of disordered thoughts I was already having. It was the sense of belonging—of finally being understood. When my parents expressed concern about my shrinking frame, the forums told me they were “just jealous.” When friends commented on my new eating habits, the community provided ready-made excuses and deflections.

These spaces operate with their own language and cultural norms. Members share “tips and tricks” for hiding disordered behaviors from family and medical professionals. They trade recommendations for appetite suppressants, laxatives, and diet pills. Achievement posts celebrate dangerous weight milestones or extended fasting periods.

Most disturbing are the “accountability partners”—relationships formed specifically to enforce disordered eating patterns. My accountability partner, a girl who called herself Lily (though I doubt that was her real name), would check in daily to ensure I hadn’t exceeded our agreed-upon calorie limit. We’d share body checks and criticize each other’s progress.

Looking back, I recognize how these communities exploit vulnerable individuals already predisposed to eating disorders. They don’t create the initial tendency, but they certainly accelerate and reinforce it. They transform isolation into belonging—but at the cost of worsening illness and delaying treatment.

BREAKTHROUGH WEIGHT LOSS DISCOVERY! 🔥 Mitolyn activates your body’s “skinny switch” that celebrities have been keeping secret!💪

Pro Anorexia Chat: When Community Becomes Dangerous

Beyond forums, pro anorexia chat rooms provided real-time interaction with others actively engaged in disordered behaviors. These spaces operated with fewer content restrictions than public forums, allowing for more explicit discussions of dangerous behaviors.

These chats normalized the abnormal. When I expressed concern about heart palpitations after three days of fasting, other users suggested electrolyte supplements—not as a way to protect my health, but as a method to continue fasting without medical consequences. When another member posted about passing out at school, the responses focused on developing cover stories rather than seeking medical attention.

What makes pro anorexia chat environments particularly dangerous is their immediacy. During moments of wavering commitment to disordered behaviors—like considering eating a forbidden food or canceling an excessive exercise session—these chats provided instant reinforcement of disorder. Someone was always online, ready to “talk you down” from recovery-oriented thoughts or actions.

The experience creates a distorted reality where the most dangerous behaviors receive the most positive reinforcement. Status in these communities often correlates with severity of illness—the thinnest, most restrictive members receiving the most admiration and attention.

My wake-up call came when a regular member of our chat group disappeared suddenly. After weeks of increasingly concerning posts about physical symptoms, she simply stopped logging in. Another member who knew her offline eventually confirmed she had been hospitalized with heart failure. She was nineteen years old.

Even this didn’t immediately break the spell. Instead, we mythologized her experience, speaking of her in reverent tones as someone who had pushed the boundaries further than the rest of us dared. It would take another year and my own medical crisis before I began questioning the warped values of these communities.

Anorexia Nervosa Binge Eating/Purging Type: Diagnostic Complexity

My own diagnosis evolved over time. What began as restrictive anorexia eventually developed into what clinicians call anorexia nervosa binge eating/purging type—a subtype of anorexia that includes periods of binging and purging behaviors while maintaining an overall pattern of restriction and weight loss.

This diagnostic complexity made treatment more challenging. Programs designed primarily for restrictive patients didn’t adequately address purging behaviors. Conversely, bulimia-focused approaches sometimes encouraged a level of regular eating that triggered intense anxiety given my anorexic thought patterns.

The diagnosis also carried additional medical risks. While restriction alone damages the body, the addition of purging creates further electrolyte imbalances that increase cardiac risks. My medical team constantly monitored potassium and other electrolyte levels, explaining that the combination of malnutrition and purging created a particularly dangerous physical state.

In treatment, I discovered many others with similar diagnostic complexity. Pure restriction or pure binge-purge patterns were actually less common than mixed presentations that evolved over time. Patients often described moving between different patterns of disordered eating while the underlying psychological drivers remained constant.

The diagnostic distinctions mattered less than understanding the function these behaviors served in my life. Restriction provided a false sense of control during periods when life felt chaotic. Binging briefly soothed emotional pain. Purging temporarily relieved anxiety and guilt. Different behaviors, same underlying needs for emotional regulation and control.

Borderline Anorexia Nervosa: The Dangerous Middle Ground

During my second treatment attempt, a dietitian used the term “borderline anorexia nervosa” to describe patients who met most diagnostic criteria for anorexia but remained just above the arbitrary weight thresholds used by insurance companies to approve higher levels of care.

This terminology highlights a dangerous reality in eating disorder treatment: patients often must deteriorate to critical levels before receiving appropriate care. This creates a perverse incentive for individuals early in illness progression to worsen in order to qualify for treatment—something I experienced firsthand when denied residential treatment because my weight was “not low enough” despite clear medical symptoms.

The concept of borderline anorexia nervosa is controversial among eating disorder specialists. Some argue it minimizes the severity of illness in patients who may be medically compromised despite not meeting arbitrary weight criteria. Others worry it pathologizes individuals experiencing transient disordered eating that might resolve without intensive intervention.

My own experience existed in this frustrating middle ground for months. Sick enough to suffer significant physical and psychological effects, but not sick enough (by insurance standards) to receive comprehensive treatment. This period represented a missed opportunity for early intervention that might have prevented the subsequent deterioration that eventually required medical hospitalization.

The eating disorder field has gradually moved toward more nuanced diagnostic approaches that consider behavioral and psychological symptoms alongside weight. However, insurance coverage often lags behind clinical best practices, creating barriers for patients in this dangerous middle ground.

Naltrexone for Binge Eating: Medication as One Recovery Tool

Medication became an unexpected component of my recovery journey. After achieving initial physical stabilization, residual binge eating symptoms persisted despite therapy and nutritional rehabilitation. My psychiatrist suggested naltrexone for binge eating—an opiate antagonist typically used for alcohol dependence that has shown some efficacy for binge behaviors.

The recommendation initially triggered skepticism. I had absorbed the common belief that eating disorders are purely psychological or willpower issues rather than brain-based conditions that might respond to medication. This perspective, I later learned, reflected stigma rather than science.

“Eating disorders are brain disorders with severe psychological and social components,” my psychiatrist explained. “Medication doesn’t replace therapy or nutrition work, but it can help create a neurochemical environment more conducive to utilizing those tools.”

Research on naltrexone for binge eating suggests it works by dampening the rewarding aspects of binge episodes rather than directly affecting appetite or metabolism. For some patients, this interruption of the reward cycle provides enough neurochemical space to implement behavioral skills that eventually become self-sustaining.

My experience with naltrexone was cautiously positive. The medication didn’t eliminate urges entirely but created a subtle buffer between impulse and action—enough space to practice the cognitive and emotional regulation skills I was learning in therapy. After approximately eight months, we gradually tapered the medication as these skills became more automatic.

Medication approaches to eating disorders remain controversial in some treatment communities. Some programs embrace psychiatric medication as an integrated component of treatment, while others minimize or discourage its use. This disagreement reflects broader tensions between biological and psychological understandings of eating disorders.

For patients considering medication options, careful consultation with clinicians familiar with both eating disorders and psychopharmacology is essential. Not all psychiatrists understand the unique medication considerations for patients with malnutrition, electrolyte imbalances, or cardiac effects from eating disorders.

Can Anorexia Lead to Diabetes? The Long-Term Physical Consequences

The physical consequences of prolonged eating disorders extend far beyond the immediate dangers of malnutrition. One question that emerged during my recovery was whether my disordered eating had created lasting metabolic damage—specifically, whether anorexia could lead to diabetes.

Medical research suggests a complicated relationship between eating disorders and diabetes risk. While anorexia initially increases insulin sensitivity, the pattern of restriction followed by reactive eating can create a metabolic rollercoaster that potentially increases diabetes risk over time. The relationship is bidirectional, with some research suggesting individuals with type 1 diabetes have higher rates of eating disorders due to the focus on dietary management.

My own post-recovery testing revealed impaired glucose tolerance—not full diabetes, but a precursor condition requiring monitoring. My endocrinologist explained that years of nutritional instability had potentially created lasting metabolic changes that might require management throughout my life.

This long-term consequence isn’t widely discussed in either pro-eating disorder spaces or early recovery resources. The focus typically remains on immediate medical stabilization rather than the potential for chronic health conditions that emerge years or decades later.

Other physical consequences emerged as my recovery progressed. Bone density scans revealed significant osteopenia—bone thinning that preceded osteoporosis but still indicated substantial skeletal damage from malnutrition and hormonal disruption. Dental problems from purging required extensive intervention. Digestive issues including delayed gastric emptying and IBS symptoms became chronic challenges.

These lasting physical effects underscored a painful truth: even with psychological recovery, the body keeps score. The belief that I could abuse my body for years without lasting consequences reflected the magical thinking characteristic of eating disorders.

Bulimia Hair Loss: Visible Signs of Invisible Struggles

Among the many physical consequences of my eating disorder, hair loss became one of the most visibly distressing. What began as increased shedding eventually progressed to noticeable thinning, particularly around my temples and crown. A dermatologist confirmed what I suspected: bulimia hair loss resulting from nutritional deficiencies and metabolic stress.

This visible symptom created a complicated psychological dynamic. On one hand, the hair loss caused significant distress, threatening the body image concerns that partially drove my eating disorder. On the other hand, it provided tangible evidence of illness that was otherwise easy to minimize or deny.

In treatment groups, I discovered hair loss was a commonly shared experience that crossed diagnostic categories. Patients with restrictive disorders, binge-purge patterns, and atypical presentations all reported similar issues. The underlying mechanisms varied—protein malnutrition, specific micronutrient deficiencies like zinc or biotin, thyroid dysfunction secondary to malnutrition, or stress-induced telogen effluvium.

Recovery brought slow improvement. Nutritional rehabilitation gradually restored normal hair growth cycles, though the process took substantially longer than expected. A treatment center dietitian explained this lag reflects the body’s triage approach to healing—prioritizing critical internal organ function before directing resources to less essential functions like hair growth.

This experience highlighted how eating disorders affect every system in the body, from the immediately life-threatening cardiac and electrolyte issues to the more visible but less medically serious dermatological effects. Recovery requires patience as these systems heal at different rates, sometimes with temporary worsening of symptoms as the body recalibrates.

Anorexia and Edema: The Counterintuitive Recovery Process

One of the most psychologically challenging aspects of early recovery was the development of edema—swelling caused by fluid retention that commonly occurs during nutritional rehabilitation. Despite being warned about this possibility, the reality of experiencing anorexia and edema simultaneously tested my commitment to recovery in ways I hadn’t anticipated.

The physiological explanation was straightforward: prolonged malnutrition causes decreased protein levels that alter fluid balance in the body. Additionally, certain hormones like aldosterone increase during starvation, promoting sodium and fluid retention. When nutrition improves, these systems temporarily overcompensate before establishing new equilibrium.

The psychological impact, however, was anything but straightforward. After years of equating body size with self-worth, the rapid swelling—particularly noticeable in my ankles, face, and abdomen—triggered intense urges to return to restriction. The eating disorder voice weaponized this normal recovery phenomenon, insisting it proved recovery was harmful.

My therapist introduced a helpful metaphor: “Think of your body like a dried-out sponge. When you first add water, it sits on the surface before being absorbed. Your tissues are the same way right now—they need time to remember how to properly process and distribute fluids.”

Understanding edema in anorexia nervosa proved crucial for staying the course during this difficult phase. Medical monitoring confirmed that despite the visible swelling, my overall health was improving—heart rate normalizing, laboratory values stabilizing, cognitive function sharpening. These objective measures provided essential counterevidence to the eating disorder’s catastrophic interpretation of body changes.

Edema in Anorexia Nervosa: Medical Management Approaches

The treatment approach to edema in anorexia nervosa differs significantly from edema management in other medical conditions. While diuretics might be prescribed for fluid retention in heart failure or certain kidney conditions, they’re generally contraindicated during eating disorder recovery due to electrolyte risks and potential for abuse.

Instead, my treatment team focused on supportive measures while allowing natural physiological processes to resolve the edema:

- Gentle movement like short walks to promote circulation

- Elevating legs when resting

- Ensuring adequate protein intake to help restore normal osmotic pressure

- Properly distributed fluid intake throughout the day rather than large amounts at once

- Compression socks for severe lower extremity swelling

- Monitoring blood pressure and electrolytes to ensure safety

The dietitian emphasized that attempting to “fix” the edema through restriction or other compensatory measures would ultimately prolong the problem by keeping my body in a stressed state. Only consistent nutrition would allow my body to rebuild the proteins and reestablish the hormonal balance needed for proper fluid regulation.

For most patients, including myself, refeeding edema resolves gradually over weeks to months as nutritional rehabilitation progresses. However, the psychological challenge often persists longer than the physical symptom itself. Body image work became especially important during this phase, developing skills to tolerate temporary physical changes without reverting to harmful behaviors.

EMDR for Weight Loss: Reframing Treatment Expectations

My search for recovery solutions led down various paths, including investigating alternative therapeutic approaches. One treatment initially caught my attention based on misleading online marketing: EMDR for weight loss. Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing is a legitimate therapy for trauma processing, but its application to weight management represents a mischaracterization that initially confused my understanding.

What I eventually learned through proper clinical guidance was that EMDR isn’t appropriate as a weight loss intervention but can be valuable for addressing underlying trauma that might contribute to disordered eating patterns. Many eating disorder patients, myself included, have histories of trauma that become intertwined with food and body issues.

My work with an EMDR-trained therapist focused on processing specific traumatic experiences that predated my eating disorder. While not directly addressing eating behaviors, this trauma work created space for other recovery interventions to work more effectively by reducing the emotional load that my eating disorder had been unsuccessfully attempting to manage.

This experience highlighted a broader pattern in eating disorder recovery: the importance of addressing underlying issues rather than focusing exclusively on weight or food behaviors. Patients looking for quick fixes or weight-centered approaches often find themselves caught in treatment cycles that address symptoms without resolving root causes.

The distinction matters because treatment expectations significantly impact outcomes. Approaching therapy with weight-focused goals often leads to disappointment and premature treatment discontinuation. Reframing recovery around emotional regulation, identity development, and values-based living creates more sustainable healing paths.

Zoloft for Eating Disorders: The Role of Psychopharmacology

Medication decisions in eating disorder treatment require careful consideration of both risks and potential benefits. When my treatment team suggested Zoloft for eating disorders, specifically to address comorbid depression and anxiety symptoms, I had significant reservations.

These concerns weren’t unfounded. Malnutrition affects medication metabolism, potentially increasing side effect risks or altering therapeutic efficacy. Additionally, weight changes sometimes associated with SSRIs like Zoloft can trigger eating disorder thoughts in vulnerable individuals.

“Medication isn’t a magic solution,” my psychiatrist explained, “but untreated depression and anxiety create additional barriers to using your therapy and nutrition skills effectively. We’re treating these conditions to create better conditions for your overall recovery work.”

After thorough discussion of risks, benefits, and alternatives, I began a conservative trial of Zoloft, starting at a lower dose than typically prescribed for patients without eating disorders. Regular monitoring included not just standard depression and anxiety assessments but also specific attention to any impacts on eating disorder thoughts or behaviors.

The results were cautiously positive. As depression symptoms improved, I found greater capacity to engage with challenging therapy work and more motivation to maintain recovery-oriented behaviors. The medication didn’t directly reduce eating disorder urges but created more psychological space to utilize the skills I was learning.

Research on zoloft for eating disorders shows mixed results depending on diagnosis, with stronger evidence for bulimia nervosa than anorexia nervosa. However, when comorbid conditions like depression or obsessive-compulsive disorder are present, medication management becomes an important consideration regardless of specific eating disorder diagnosis.

OA Find a Meeting: The Role of Support Groups in Recovery

Professional treatment formed the foundation of my recovery, but peer support through groups like Overeaters Anonymous provided crucial supplemental support, particularly during transition periods between treatment levels. The OA Find a Meeting tool became a valuable resource for locating appropriate meetings during these vulnerable phases.

My experience with OA was mixed. Certain aspects of the program—particularly the focus on abstinence from “trigger foods” and emphasis on surrendering control—sometimes conflicted with my clinical treatment plan emphasizing flexible, normalized eating patterns. However, the community aspect and opportunity to connect with others further along in recovery provided hope and practical strategies for navigating daily challenges.

I learned to approach support groups selectively, identifying meetings that were “recovery-oriented” rather than potentially triggering. Specifically, I sought out meetings that:

- Emphasized emotional and spiritual recovery rather than weight or food plans

- Welcomed participants regardless of specific diagnosis or body size

- Discouraged “war stories” that detailed specific behaviors

- Focused on solution-oriented sharing rather than problem rumination

- Incorporated professional guidance alongside peer support

The availability of virtual meetings dramatically expanded access options, particularly valuable for those in rural areas or with transportation limitations. The OA website’s meeting finder included search filters for special focus meetings, including those specifically for eating disorder recovery rather than general food addiction or weight management.

Support groups work best as a complement to professional treatment rather than a replacement. Members who treated peer support as their primary intervention often struggled with medical and nutritional aspects of recovery that require specialized expertise. However, the experiential knowledge shared in these communities offers valuable practical insights that complement clinical approaches.

Eating Disorder VA Rating: Navigating Treatment Access

The financial aspects of eating disorder treatment create significant barriers to recovery for many patients. My exploration of the eating disorder VA rating system reflected a broader struggle to access appropriate care within insurance-constrained systems.

For veterans, the VA’s approach to eating disorder treatment has evolved significantly in recent years. Previously classified primarily as mental health conditions, eating disorders now receive more comprehensive medical recognition within the VA system, potentially qualifying for higher disability ratings that reflect their serious physical impacts.

However, navigating this system requires persistence and advocacy. My initial assessment minimized the medical severity of my condition until more comprehensive testing revealed cardiac abnormalities and metabolic disruption that clearly demonstrated service impact. This experience mirrors the broader healthcare system’s tendency to underestimate eating disorder severity until crisis points emerge.

For patients without VA access, insurance challenges create similar obstacles. Many insurance providers limit treatment duration based on arbitrary timeframes rather than clinical recommendations, leading to premature discharge and increased relapse risk. The mental health parity laws designed to ensure equal coverage for psychiatric and physical conditions remain inconsistently implemented for eating disorders despite their clear medical components.

Community resources can partially bridge these gaps. University research programs sometimes offer reduced-cost treatment while testing new approaches. Advocacy organizations like the National Eating Disorders Association maintain treatment scholarship databases. Some treatment centers offer sliding scale fees or limited charity care slots, though demand far exceeds availability.

The financial reality of eating disorders creates a profoundly unjust system where recovery access correlates more strongly with financial resources than medical need. Systemic change through continued advocacy for insurance reform, expanded public health programs, and research funding represents the only sustainable solution to this treatment gap.

Eating Disorder Recovery Center: The Treatment Continuum

My recovery journey involved multiple levels of care across different treatment settings. The eating disorder recovery center model typically includes a spectrum of options tailored to illness severity and recovery stage:

- Inpatient medical hospitalization for acute medical stabilization

- Residential treatment for subacute medical issues requiring 24-hour supervision

- Partial hospitalization programs (PHP) providing structured treatment during daytime hours

- Intensive outpatient programs (IOP) offering several treatment sessions weekly

- Standard outpatient care with individual providers coordinating care

Movement between these levels ideally creates a step-down approach allowing gradual increase in autonomy as recovery skills develop. My experience included multiple cycles through these levels as my recovery followed a non-linear path with periods of progress and setbacks.

The most effective programs maintained philosophical and treatment consistency across levels, allowing patients to work with familiar approaches and sometimes the same treatment providers as they transitioned between intensities of care. This continuity significantly reduced the disruption of level changes and improved treatment engagement.

Program quality varies significantly across centers. The most effective treatments incorporated evidence-based approaches like Enhanced Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT-E), Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT), Family-Based Treatment for younger patients, and nutritional rehabilitation protocols based on current research rather than outdated practices.

The recovery center environment itself significantly impacts treatment effectiveness. Facilities that physically resemble hospitals with institutional aesthetics sometimes reinforce illness identity, while those providing more homelike settings facilitate practice of recovery skills in normalized environments. Similarly, programs that balance necessary monitoring with appropriate autonomy better prepare patients for real-world recovery challenges.

For individuals seeking treatment, researching program approaches, staff credentials, and outcome measures provides essential information beyond marketing materials. Speaking with program alumni, when possible, offers valuable perspective on the lived experience of particular programs beyond their stated philosophies.

Recovery Is Possible: A Personal Conclusion

Eight years after first encountering those pro-anorexia websites, my relationship with food and body has transformed. Recovery isn’t perfect—certain situations still trigger disordered thoughts, and stress sometimes awakens old urges. However, these experiences exist as background noise rather than driving forces in my life.

The physical consequences of years of malnutrition and purging require ongoing management. Regular check-ups monitor the cardiac and bone density issues that developed during my illness. Digestive problems persist but have improved with consistent nutrition and stress management. Most noticeably, the cognitive clarity that returned with recovery revealed how profoundly the eating disorder had affected my thinking beyond just food and body concerns.

What surprised me most about recovery was rediscovering interests and aspects of identity that had been subsumed by the eating disorder. Photography, community volunteering, and professional pursuits gradually replaced the singular focus on food and body that had consumed my late teens and early twenties. Relationships deepened as I became capable of true presence rather than constant distraction by eating disorder thoughts.

For those still embedded in eating disorder communities or trapped in the cycle of illness, please know that recovery—while challenging and imperfect—offers a quality of life incomparably better than the false promises of eating disorders. The identity and community found in illness are poor substitutes for the genuine connection and purpose available when food and body concerns assume appropriate rather than central importance in your life.

Recovery requires courage, persistence, and support. It rarely happens perfectly or in a straight line. But step by step, meal by challenging meal, a different life becomes possible. Eight years after seeking destructive “support” in pro-anorexia spaces, I now find genuine connection in recovery communities dedicated to building lives worth living beyond the narrow confines of eating disorders.

This article reflects personal experience and is not intended as medical advice. If you’re struggling with disordered eating, please reach out to qualified healthcare providers for appropriate diagnosis and treatment.

Looking to melt that stubborn belly fat FAST? 🔥 Java Burn is your secret weapon! Just mix this tasteless powder into your morning coffee and watch the magic happen! 💪

- Unleash Explosive Motivation: Powerful Fitness Quotes Backed By Science

- Jelly Roll Weight Loss: Medical Analysis of a 150-Pound Transformation

- Danielle Macdonald Weight Loss: Her Inspiring Health Transformation

- Med Spa Weight Loss: The Truth Behind Modern Solutions

- Planet Fitness Smith Machine Bar Weight: What You Need to Know

- Elevate Health and Wellness Semaglutide: Transforming Weight Management

- Cupping Treatment for Weight Loss: Does This Ancient Practice Work?

- Tirzepatide Weight Loss Before and After: My 78-Pound Journey

- Ana and Mia: The Dark World of Eating Disorders and Recovery Paths

- Lipo Alternative Guide: 15 Fat Reduction Methods That Actually Work

- Everyday Fitness: Making Active Living Work for You

- Java Burn: The Coffee Supplement Everyone’s Talking About

- Mitolyn Reviews 2025: My 90-Day Test of This Trendy Metabolism Supplement

- Weight Loss Plateau Breaking Techniques: What Finally Worked After Everything Else Failed

- My Struggle and Success: Weight Loss with Thyroid Medication

- The Night Shift Nightmare: My Real Journey with Weight Loss for Shift Workers Schedule

- Fighting the Battle: My Raw Truth About Weight Loss During Menopause Hormones

- My Personal Journey with Weight Loss for Autoimmune Conditions: What Actually Works

- Live Chat Jobs with Flexible Hours for Moms: Work Smart, Mom Hard

- Easy Live Chat Jobs for Beginners in 2025: My Take on Getting Started

Leave a comment